Now let me look at characterization in a traditional way by giving examples of them from novels that are popularly common.

Flat character - "Flat characters are two-dimensional in that they are relatively uncomplicated and do not change throughout the course of a work. By contrast, round characters are complex and undergo development, sometimes sufficiently to surprise the reader." (https://www.britannica.com/art/flat-character)

Typical examples are villains and sidekicks or friends of the hero. Horatio is always loyal to Hamlet right to the end, and loyalty is his characteristic from beginning to end with no change, except to be a foil for Hamlet to say things to him like " there is more in heaven and earth than what is written of in your books, Horatio" and "tell my story." We do not know if he does or not but presume he will, as the story comes to us from Saxo-Grammaticus and Shakespeare and not Horatio, interestingly enough. Such characters are also called stock characters and stereotypes, static ones.

Dr Watson is also the perfect foil or sidekick.

The perfect villain is Moriarty. He is the antagonist who even kills the protagonist, hero, but fails.

Round characters are dynamic and become archetypal, are often major or main and hero, heroine and protagonist.

Thomas Gradgrind in Hard Times by Charles Dickens is a round, developing, changing character, who becomes a hero by virtue of a change of heart. He thus becomes a protagonist and not just a central character. This is true also of Louisa Gradgrind who evolves into a heroine over time. But minor characters too change and evolve or degenerate, as Rachael becomes more angelic, despite her suffering and Tom Gradgrind in the course of the novel grows progressively worse.

As usual, while talking of these things, I go over familiar ground so get bored but more interesting is absent character, and the character of non-living things and living creatures others than human beings that make novels interesting. Another thing that really interests us is the comic character. They are memorable when pulled off well, Falstaff is a famous example. My examples come from drama twice, here, hope you don't mind. The jester, the clown, the harlequin, the fool, Punch, they are a type that enthralls us.

To come back to Merrylegs, the dog, in Hard Times.

‘Thquire,—you don’t need to be told that dogth ith wonderful animalth.’

‘Their instinct,’ said Mr. Gradgrind, ‘is surprising.’

‘Whatever you call it—and I’m bletht if I know what to call it’—said Sleary, ‘it ith athtonithing. The way in whith a dog’ll find you—the dithtanthe he’ll come!’

‘His scent,’ said Mr. Gradgrind, ‘being so fine.’

‘I’m bletht if I know what to call it,’ repeated Sleary, shaking his head, ‘but I have had dogth find me, Thquire, in a way that made me think whether that dog hadn’t gone to another dog, and thed, “You don’t happen to know a perthon of the name of Thleary, do you? Perthon of the name of Thleary, in the Horthe-Riding way—thtout man—game eye?” And whether that dog mightn’t have thed, “Well, I can’t thay I know him mythelf, but I know a dog that I think would be likely to be acquainted with him.” And whether that dog mightn’t have thought it over, and thed, “Thleary, Thleary! O yeth, to be thure! A friend of mine menthioned him to me at one time. I can get you hith addreth directly.” In conthequenth of my being afore the public, and going about tho muth, you thee, there mutht be a number of dogth acquainted with me, Thquire, that I don’t know!’

Mr. Gradgrind seemed to be quite confounded by this speculation.

‘Any way,’ said Sleary, after putting his lips to his brandy and water, ‘ith fourteen month ago, Thquire, thinthe we wath at Chethter. We wath getting up our Children in the Wood one morning, when there cometh into our Ring, by the thtage door, a dog. He had travelled a long way, he wath in a very bad condithon, he wath lame, and pretty well blind. He went round to our children, one after another, as if he wath a theeking for a child he know’d; and then he come to me, and throwd hithelf up behind, and thtood on hith two forelegth, weak ath he wath, and then he wagged hith tail and died. Thquire, that dog wath Merrylegth.’

‘Sissy’s father’s dog!’

‘Thethilia’th father’th old dog. Now, Thquire, I can take my oath, from my knowledge of that dog, that that man wath dead—and buried—afore that dog come back to me. Joth’phine and Childerth and me talked it over a long time, whether I thould write or not. But we agreed, “No. There’th nothing comfortable to tell; why unthettle her mind, and make her unhappy?” Tho, whether her father bathely detherted her; or whether he broke hith own heart alone, rather than pull her down along with him; never will be known, now, Thquire, till—no, not till we know how the dogth findth uth out!’

‘She keeps the bottle that he sent her for, to this hour; and she will believe in his affection to the last moment of her life,’ said Mr. Gradgrind.

‘It theemth to prethent two thingth to a perthon, don’t it, Thquire?’ said Mr. Sleary, musing as he looked down into the depths of his brandy and water: ‘one, that there ith a love in the world, not all Thelf-interetht after all, but thomething very different; t’other, that it hath a way of its own of calculating or not calculating, whith somehow or another ith at leatht ath hard to give a name to, ath the wayth of the dogth ith!’ (https://www.gutenberg.org/files/786/786-h/786-h.htm#page216)

And absent characters? Sissy's father Jupe is one.

Godot is powerful as he is absent, back to drama.

The more absent a character the more powerful. In Jane Eyre, there is a character who is absent mostly, Rochester's wife, and her maid Grace Poole is suspected to be her, but this "madwoman in the attic" who set the house on fire after finding out that Jane is to marry Rochester on seeing her bridal gown and other wedding finery, a fire in which Rochester is badly wounded, is a very powerful presence, so powerful as to get another writer Jean Rhys to write a novel on her, called The Wide Saragasso Sea.

The tragic heroine is powerful, witness Ophelia.

So is the femme fatale, witness Medusa.

The heroine who succeeds is powerful, as in the story of Jane Eyre with her "reader, I married him" at the end, making us feel thrilled. The one who does not, like Catherine, in Wuthering Heights is too. The woman of loose virtue fascinates us as in Madame Bovary and Nana, or at leat fascinated men, and women love witches, as in Macbeth.

But which character do I love the most among women. Hester Prynne, the woman in the Scarlet Letter, and her child Pearl hold endless fascination for me.

And the most chilling villain? Roger Chillingworth of Scarlet Letter.

Chapter 15.

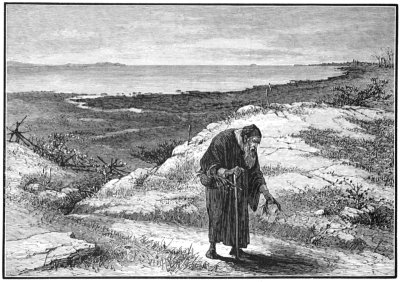

Roger Chillingworth—a deformed old figure, with a face that haunted men's memories longer than they liked—took leave of Hester Prynne, and went stooping away along the earth. He gathered here and there an herb, or grubbed up a root, and put it into the basket on his arm. His gray beard almost touched the ground, as he crept onward. Hester gazed after him a little while, looking with a half-fantastic curiosity to see whether the tender grass of early spring would not be blighted beneath him, and show the wavering track of his footsteps, sere and brown, across its cheerful verdure. She wondered what sort of herbs they were, which the old man was so sedulous to gather. Would not the earth, quickened to an evil purpose by the sympathy of his eye, greet him with poisonous shrubs, of species hitherto unknown, that would start up under his fingers? Or might it suffice him, that every wholesome growth should be converted into something deleterious and malignant at his touch? Did the sun, which shone so brightly everywhere else, really fall upon him? Or was there, as it rather seemed, a circle of ominous shadow moving along with his deformity, whichever way he turned himself? And whither was he now going? Would he not suddenly sink into the earth, leaving a barren and blasted spot, where, in due course of time, would be seen deadly nightshade, dogwood, henbane, and whatever else of vegetable wickedness the climate could produce, all flourishing with hideous luxuriance? Or would he spread bat's wings and flee away, looking so much the uglier, the higher he rose towards heaven?

“Be it sin or no,” said Hester Prynne, bitterly, as she still[214] gazed after him, “I hate the man!”

She upbraided herself for the sentiment, but could not overcome or lessen it. Attempting to do so, she thought of those long-past days, in a distant land, when he used to emerge at eventide from the seclusion of his study, and sit down in the[215] firelight of their home, and in the light of her nuptial smile. He needed to bask himself in that smile, he said, in order that the chill of so many lonely hours among his books might be taken off the scholar's heart. Such scenes had once appeared not otherwise than happy, but now, as viewed through the dismal medium of her subsequent life, they classed themselves among her ugliest remembrances. She marvelled how such scenes could have been! She marvelled how she could ever have been wrought upon to marry him! She deemed it her crime most to be repented of, that she had ever endured, and reciprocated, the lukewarm grasp of his hand, and had suffered the smile of her lips and eyes to mingle and melt into his own. And it seemed a fouler offence committed by Roger Chillingworth, than any which had since been done him, that, in the time when her[216] heart knew no better, he had persuaded her to fancy herself happy by his side.

“Yes, I hate him!” repeated Hester, more bitterly than before. “He betrayed me! He has done me worse wrong than I did him!”

Let men tremble to win the hand of woman, unless they win along with it the utmost passion of her heart! Else it may be their miserable fortune, as it was Roger Chillingworth's, when some mightier touch than their own may have awakened all her sensibilities, to be reproached even for the calm content, the marble image of happiness, which they will have imposed upon her as the warm reality. But Hester ought long ago to have done with this injustice. What did it betoken? Had seven long years, under the torture of the scarlet letter, inflicted so much of misery, and wrought out no repentance?

The emotions of that brief space, while she stood gazing after the crooked figure of old Roger Chillingworth, threw a dark light on Hester's state of mind, revealing much that she might not otherwise have acknowledged to herself.

He being gone, she summoned back her child.

“Pearl! Little Pearl! Where are you?”

Pearl, whose activity of spirit never flagged, had been at no loss for amusement while her mother talked with the old gatherer of herbs. At first, as already told, she had flirted fancifully with her own image in a pool of water, beckoning the phantom forth, and—as it declined to venture—seeking a passage for herself into its sphere of impalpable earth and unattainable sky. Soon finding, however, that either she or the image was unreal, she turned elsewhere for better pastime. She made little boats out of birch-bark, and freighted them with snail-shells, and sent out more ventures on the mighty deep than any merchant in New England; but the larger part of them foundered near the shore. She seized a live horseshoe by the tail, and made prize of several five-fingers, and laid out a jelly-fish to melt in the warm sun. Then she took up the white foam, that streaked the line of the advancing tide, and threw it upon the breeze, scampering after it, with winged footsteps, to catch the great snow-flakes ere they fell. Perceiving a flock of beach-birds, that fed and fluttered along the shore, the naughty child picked up her apron full of pebbles, and, creeping from rock to rock after these small sea-fowl, displayed remarkable dexterity in pelting them. One little gray bird, with a white breast, Pearl was almost sure, had been hit by a pebble, and fluttered away with a broken wing. But then the elf-child sighed, and gave up her[218] sport; because it grieved her to have done harm to a little being that was as wild as the sea-breeze, or as wild as Pearl herself.

Her final employment was to gather sea-weed, of various kinds, and make herself a scarf, or mantle, and a head-dress, and thus assume the aspect of a little mermaid. She inherited her mother's gift for devising drapery and costume. As the last touch to her mermaid's garb, Pearl took some eel-grass, and imitated, as best she could, on her own bosom, the decoration with which she was so familiar on her mother's. A letter,—the letter A,—but freshly green, instead of scarlet! The child bent her chin upon her breast, and contemplated this device with strange interest; even as if the one only thing for which she had been sent into the world was to make out its hidden import.

“I wonder if mother will ask me what it means?” thought Pearl.

Just then, she heard her mother's voice, and flitting along as lightly as one of the little sea-birds, appeared before Hester Prynne, dancing, laughing, and pointing her finger to the ornament upon her bosom.

“My little Pearl,” said Hester, after a moment's silence, “the green letter, and on thy childish bosom, has no purport. But dost thou know, my child, what this letter means which thy mother is doomed to wear?”

“Yes, mother,” said the child. “It is the great letter A. Thou hast taught me in the horn-book.”

Hester looked steadily into her little face; but, though there was that singular expression which she had so often remarked in her black eyes, she could not satisfy herself whether Pearl really attached any meaning to the symbol. She felt a morbid desire to ascertain the point.[219]

“Dost thou know, child, wherefore thy mother wears this letter?”

“Truly do I!” answered Pearl, looking brightly into her mother's face. “It is for the same reason that the minister keeps his hand over his heart!”

“And what reason is that?” asked Hester, half smiling at the absurd incongruity of the child's observation; but, on second thoughts, turning pale. “What has the letter to do with any heart, save mine?”

“Nay, mother, I have told all I know,” said Pearl, more seriously than she was wont to speak. “Ask yonder old man whom thou hast been talking with! It may be he can tell. But in good earnest now, mother dear, what does this scarlet letter mean?—and why dost thou wear it on thy bosom?—and why does the minister keep his hand over his heart?”

She took her mother's hand in both her own, and gazed into her eyes with an earnestness that was seldom seen in her wild and capricious character. The thought occurred to Hester, that the child might really be seeking to approach her with childlike confidence, and doing what she could, and as intelligently as she knew how, to establish a meeting-point of sympathy. It showed Pearl in an unwonted aspect. Heretofore, the mother, while loving her child with the intensity of a sole affection, had schooled herself to hope for little other return than the waywardness of an April breeze; which spends its time in airy sport, and has its gusts of inexplicable passion, and is petulant in its best of moods, and chills oftener than caresses you, when you take it to your bosom; in requital of which misdemeanors, it will sometimes, of its own vague purpose, kiss your cheek with a kind of doubtful tenderness, and play gently with your hair, and then[220] be gone about its other idle business, leaving a dreamy pleasure at your heart. And this, moreover, was a mother's estimate of the child's disposition. Any other observer might have seen few but unamiable traits, and have given them a far darker coloring. But now the idea came strongly into Hester's mind, that Pearl, with her remarkable precocity and acuteness, might already have approached the age when she could be made a friend, and intrusted with as much of her mother's sorrows as could be imparted, without irreverence either to the parent or the child. In the little chaos of Pearl's character there might be seen emerging—and could have been, from the very first—the steadfast principles of an unflinching courage,—an uncontrollable will,—a sturdy pride, which might be disciplined into self-respect,—and a bitter scorn of many things, which, when examined, might be found to have the taint of falsehood in them. She possessed affections, too, though hitherto acrid and disagreeable, as are the richest flavors of unripe fruit. With all these sterling attributes, thought Hester, the evil which she inherited from her mother must be great indeed, if a noble woman do not grow out of this elfish child.

Pearl's inevitable tendency to hover about the enigma of the scarlet letter seemed an innate quality of her being. From the earliest epoch of her conscious life, she had entered upon this as her appointed mission. Hester had often fancied that Providence had a design of justice and retribution, in endowing the child with this marked propensity; but never, until now, had she bethought herself to ask, whether, linked with that design, there might not likewise be a purpose of mercy and beneficence. If little Pearl were entertained with faith and trust, as a spirit messenger no less than an earthly child, might it not be her[221] errand to soothe away the sorrow that lay cold in her mother's heart, and converted it into a tomb?—and to help her to overcome the passion, once so wild, and even yet neither dead nor asleep, but only imprisoned within the same tomb-like heart?

Such were some of the thoughts that now stirred in Hester's mind, with as much vivacity of impression as if they had actually been whispered into her ear. And there was little Pearl, all this while, holding her mother's hand in both her own, and turning her face upward, while she put these searching questions, once, and again, and still a third time.

“What does the letter mean, mother?—and why dost thou wear it?—and why does the minister keep his hand over his heart?”

“What shall I say?” thought Hester to herself. “No! If this be the price of the child's sympathy, I cannot pay it.”

Then she spoke aloud.

“Silly Pearl,” said she, “what questions are these? There are many things in this world that a child must not ask about. What know I of the minister's heart? And as for the scarlet letter, I wear it for the sake of its gold-thread.”

In all the seven bygone years, Hester Prynne had never before been false to the symbol on her bosom. It may be that it was the talisman of a stern and severe, but yet a guardian spirit, who now forsook her; as recognizing that, in spite of his strict watch over her heart, some new evil had crept into it, or some old one had never been expelled. As for little Pearl, the earnestness soon passed out of her face.

But the child did not see fit to let the matter drop. Two or three times, as her mother and she went homeward, and as often at supper-time, and while Hester was putting her to bed,[222] and once after she seemed to be fairly asleep, Pearl looked up, with mischief gleaming in her black eyes.

“Mother,” said she, “what does the scarlet letter mean?”

And the next morning, the first indication the child gave of being awake was by popping up her head from the pillow, and making that other inquiry, which she had so unaccountably connected with her investigations about the scarlet letter:—

“Mother!—Mother!—Why does the minister keep his hand over his heart?”

“Hold thy tongue, naughty child!” answered her mother, with an asperity that she had never permitted to herself before. “Do not tease me; else I shall shut thee into the dark closet!” (https://www.gutenberg.org/files/25344/25344-h/25344-h.htm)

And the hero. Gilgamesh and Achilles. No need to look further though both are not from novels.